Building an On-Device Recommendation Engine SDK for Android

Where This Started

A few years back, I participated in a hackathon. Built use case around hyper-personalisation — something that could tailor product recommendations for individual users in real time. I built a rule-based engine. Category affinity, brand preferences, basic keyword matching. It scored products based on what the user had clicked on and purchased. It worked. But it was entirely rule-based.

That hackathon planted a question I kept coming back to over the years — why does personalisation need a server at all?

Think about it. The user’s entire interaction history — every view, click, add-to-cart, purchase — happens on their phone. The phone already has all the data. Shipping it to a server, processing it there, and sending recommendations back adds latency, cost, and a hard dependency on network availability. Users in poor connectivity areas get no recommendations. Users on first launch get nothing until the server catches up.

What if the recommendation engine ran on the device itself?

I’ve been an Android developer for 10 years. I knew what it would take to build this — behavior scoring, text classification, collaborative filtering, persistence across sessions. But building all of that as a side project was a time commitment I could never justify. So the idea sat there.

Then I got access to Claude Code, and this went from a side project to a working SDK in a day.

What I Built

An Android SDK — recsdk — that any app can drop in to get personalised product recommendations. No backend. No API integration on the SDK side. No user data leaving the device.

The client app does three things:

RecoEngine.init(context, RecoConfig())

RecoEngine.feedItems(products.map { it.toRecoItem() })

RecoEngine.trackEvent(EventType.CLICK, productId)

val recommendations = RecoEngine.getRecommendations()

That’s the entire integration. The SDK handles everything else — storing events, building user profiles, scoring products, ranking results.

What This Means for Product Teams

If you’re running an e-commerce app, a content platform, or any product with a catalog — here’s what this gives you:

No infrastructure cost. No recommendation server to deploy or maintain. No ML pipeline. No data warehouse for user behavior. The phone handles it.

Works offline. Users in poor connectivity areas still get personalised recommendations. The profile and models are on-device.

Privacy by design. User behavior data never leaves the device. No GDPR data processing agreements needed for the recommendation engine. No user data flowing to third-party services.

Minutes to integrate. Three method calls. One data mapping function. No new permissions, no background services, no server-side changes. A developer can have it running in their app in under an hour.

Scales to zero cost. Whether you have 1,000 users or 10 million users, the recommendation computation cost is zero on your infrastructure. Each phone runs its own engine.

The trade-off is that recommendations are per-device, not cross-device. A user’s profile on their phone doesn’t sync to their tablet. That’s a solvable problem (profile export/import is on the roadmap), but it’s worth noting.

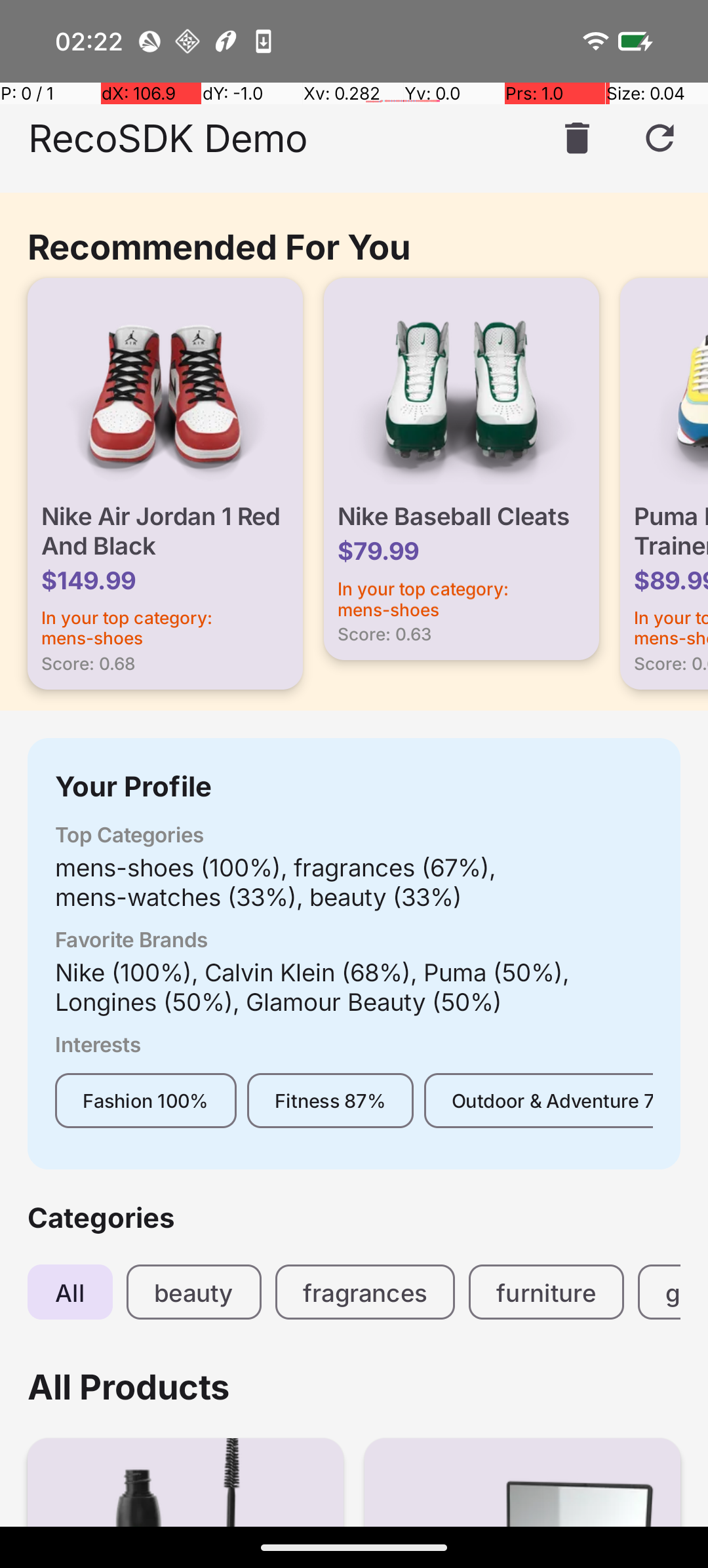

The demo app showing personalised recommendations, user profile, and category browsing — all powered on-device.

The Scoring System

Every user interaction has a weight:

| Event | Weight |

|---|---|

| VIEW | 1.0 |

| SEARCH | 1.5 |

| CLICK | 2.0 |

| ADD_TO_CART | 4.0 |

| FAVORITE | 5.0 |

| PURCHASE | 8.0 |

A purchase signal is 8x stronger than a view. Makes sense — someone buying a product tells you far more about their preferences than someone scrolling past it.

These weights decay over time. An exponential half-life (configurable, default 7 days) ensures recent behavior matters more than something from two months ago. The user’s taste evolves, and the profile reflects that.

From these weighted events, the SDK builds a user profile across three dimensions — category affinity, brand affinity, and interest tags. Interest tags are detected through text classification: the SDK scans product titles and descriptions against keyword dictionaries covering 16 categories like Vegan, Fitness, Tech, Premium, Budget, and so on.

Everything persists in Room. Kill the app, relaunch next week — the profile is still there.

Adding Machine Learning

The rule-based scoring from my hackathon days was the starting point. It catches obvious preferences — if you keep buying Nike, you probably like Nike. But it misses patterns that only emerge from behavioral data.

I added two ML engines:

Co-Occurrence Engine — This learns which products get interacted with together. If users who click on “iPhone 15” also click on “AirPods Pro” and “MagSafe Charger,” the engine captures that relationship. It groups events within a 24-hour window, pairs items from the same session, and weights pairs by event strength. A purchase-purchase pair (8 x 8 = 64) is a much stronger signal than a view-view pair (1 x 1 = 1).

TF-IDF Engine — Each product’s text (title, description, category, brand, tags) becomes a sparse vector using term frequency-inverse document frequency. When a user interacts with products, the engine builds a “user embedding” — a weighted average of those item vectors — and scores candidates by cosine similarity against it.

Both are optional. Toggle them off in config and the SDK falls back to pure rule-based scoring. The ranking weights redistribute automatically.

With ML enabled, the ranking splits 50-50 between rule-based and ML strategies:

Category(0.20) + Brand(0.15) + Tags(0.15) + CoOccurrence(0.25) + Semantic(0.25)

Where TF-IDF Falls Short

TF-IDF works on word overlap. “Running shoes” vs “Running sneakers” — some overlap, decent similarity. But “Running shoes” vs “Jogging sneakers” — almost no shared words, near-zero similarity. Same product category, same user intent, but TF-IDF can’t see it.

This shows up constantly in real product catalogs:

- “Wireless earbuds” vs “Bluetooth headphones”

- “Laptop stand” vs “Notebook riser”

- “Moisturizing cream” vs “Hydrating lotion”

- “Protein bar” vs “Energy snack”

A user who buys “organic almond milk” is probably interested in “plant-based oat milk.” TF-IDF misses the connection because the words are different. These aren’t edge cases — they’re the norm in any catalog with products from multiple vendors describing the same thing differently.

I needed a model that understands meaning, not just word counts.

Adding TFLite Semantic Embeddings

TFLite was the obvious choice for on-device inference. But the concern with adding any ML model to an SDK is size. If integrating my SDK adds 50MB to the client’s APK, that’s a hard sell.

Here’s how I addressed it:

Separate Gradle module. The core recsdk has zero ML dependencies. TFLite lives in recsdk-tflite, a separate module. Clients who don’t want it don’t include it. Their APK stays the same size.

Small model. Universal Sentence Encoder via MediaPipe is about 6MB. The MediaPipe text runtime adds another 4MB. Total cost: ~10MB for an engine that understands natural language.

On-device inference. No API calls. No latency. No user data leaving the phone. The phone’s CPU handles the embedding computation directly.

One-line integration. A client already using the SDK adds one field to their config:

RecoEngine.init(context, RecoConfig(

embeddingProvider = TfLiteEmbeddingProvider(context)

))

That’s it. The SDK detects the provider, swaps out TF-IDF for dense embeddings internally. Storage, scoring, ranking — all unchanged.

Now “running shoes” and “jogging sneakers” produce similar embeddings because they mean the same thing. The model has learned semantic relationships from its training data.

The Module Boundary Problem

There’s an architectural challenge worth calling out because it applies to anyone building multi-module Android SDKs.

All the SDK’s internal types — EmbeddingDao, EventEntity, ScoringStrategy, TimeProvider — use Kotlin’s internal visibility. They’re accessible within recsdk but invisible to recsdk-tflite. So the TFLite module can’t implement the scoring interface or write to the database directly.

The solution is a provider pattern:

-

A public

EmbeddingProviderinterface with two methods —embedText(text): FloatArrayanddimensions(): Int. No Room, no DAOs, no internal types. -

An internal

EmbeddingBridgeinsiderecsdkthat wraps the provider. It callsprovider.embedText(), stores the vectors in Room viaEmbeddingDao, computes user embeddings, and handles similarity caching. It implements the sameSimilarityEngineinterface thatTfIdfEngineimplements. -

RecoEnginechecks if anembeddingProvideris configured. If yes, it creates anEmbeddingBridge. If no, it creates aTfIdfEngine. The scorer downstream doesn’t know or care which one it’s talking to.

recsdk-tflite recsdk (internal)

┌─────────────────┐ ┌──────────────────────┐

│ TfLiteEmbedding │ FloatArray │ EmbeddingBridge │

│ Provider │ ──────────> │ stores to Room │

│ │ │ computes user emb │

│ implements │ │ caches similarity │

│ EmbeddingProvider│ │ │

└─────────────────┘ │ implements │

│ SimilarityEngine │

└──────────────────────┘

│

┌──────────────────────┐

│ SemanticSimilarity │

│ Scorer │

└──────────────────────┘

Existing clients are unaffected. No migration path. The TF-IDF fallback works exactly as before.

Semantic Classification

Once you have an embedding model on-device, text classification improves too.

The keyword-based classifier tags products by word matching — “vegan” in the title gets the Vegan tag. But “Organic Quinoa Bowl” has no keyword match for vegan, even though it clearly is.

SemanticClassifier pre-computes embeddings for category descriptions (“vegan plant-based food without animal products”) and measures cosine similarity against each product’s embedding. Products get classified by meaning. “Cashew Cheese Pizza” gets tagged as vegan without the word appearing anywhere in its listing.

This also eliminates the maintenance problem. With keywords, someone has to keep updating the dictionaries. With semantic classification, the model handles synonyms, new phrasings, and product descriptions it’s never seen before.

What I Took Away From This

The hackathon version of this idea was rule-based and server-dependent. That was a few years ago. Building the on-device version with ML and TFLite semantic embeddings — that happened in a day with Claude Code.

I designed the architecture. Every decision — the provider pattern for module boundaries, choosing MediaPipe over raw TFLite, keeping the core SDK dependency-free, the strategy pattern for scoring — those were mine. Claude Code turned those decisions into working, tested code at a pace that wouldn’t have been possible otherwise.

The abstraction layer turned out to be the most important decision. Adding TFLite support to a system designed with SimilarityEngine as a pluggable interface meant implementing one class and writing one bridge. The scoring, storage, and ranking layers didn’t change at all.

How Integration Works for Client Apps

This was a design constraint from day one. If an SDK requires the client to restructure their data layer or change their architecture, adoption drops. Nobody wants to refactor their app to try a recommendation engine.

So the contract is minimal. The client maps their product model to RecoItem:

RecoItem(

id = product.id,

title = product.name,

description = product.description,

category = product.category,

brand = product.brand,

price = product.price,

tags = product.tags

)

Most e-commerce apps already have these fields. The mapping is usually a one-liner extension function.

Event tracking is a single method call wherever the client handles user interactions — product detail screen opens, add-to-cart button tapped, purchase confirmed. No new UI components. No background services to register. No permissions to declare.

The SDK initialises in Application.onCreate(), persists everything in its own Room database (separate from the client’s), and runs all heavy computation on background coroutines. The main thread stays clean.

For teams evaluating this — the integration surface is three method calls. No server to deploy, no API keys to manage, no data pipeline to maintain. The recommendation quality improves automatically as the user interacts with the app.

What’s Next

- Benchmarking with large catalogs (10k+ items)

- A/B testing framework to measure recommendation quality

- Session-based recommendations for anonymous users

- Profile export/import for cross-device sync

- Domain-specific embedding models — swap in specialised models for fashion, food, electronics

The architecture is pluggable. Most of these are interface implementations, not rewrites.

Years of “I should build that someday” — done in a day. What a time to be alive.

The source code is available on GitHub.